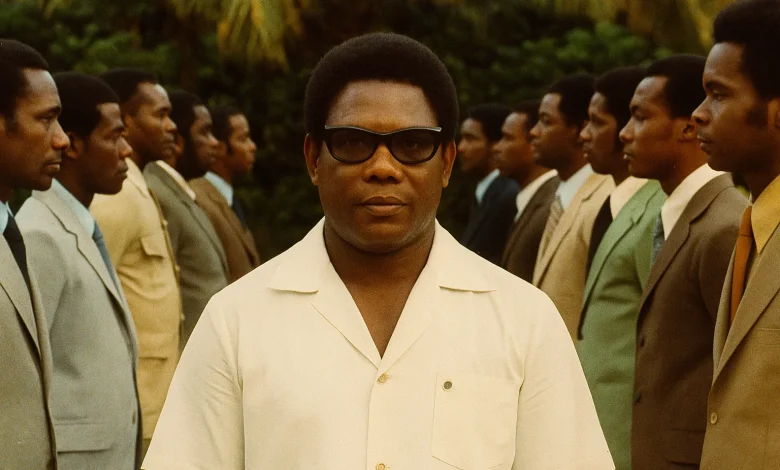

Patrick John’s Dynamic 21

Patrick John’s ‘Dynamic 21’ refers to the team of 21 Dominica Labour Party (DLP) candidates led by Patrick John during the 1975 general election, a slogan symbolising the party’s drive for national development and independence. The term became synonymous with the DLP’s sweeping parliamentary dominance in the mid-1970s, marking the height of the Labour government’s power just before the turbulence that led to the May 29th 1979 Uprising and the fall of John’s administration.

Origins and Context of Patrick John’s Dynamic 21

The “Dynamic 21” emerged following the 1975 general election, the first national poll held after Edward Oliver LeBlanc’s retirement as Premier in 1974. Patrick John, who succeeded LeBlanc, inherited a divided yet politically energised country entering a new era of constitutional maturity.

Under John’s leadership, the Labour Party campaigned on a platform of modernisation, industrialisation, and national pride. The “Dynamic 21” slogan symbolised a new generation of Labour politicians who were younger, ambitious, and determined to move Dominica toward full sovereignty. The term captured both the number of DLP parliamentarians and the government’s message of energetic progress.

Composition of the Dynamic 21

The group included several prominent figures who would shape Dominica’s political landscape for years to come. Notable members of the Dynamic 21 included:

- James Oliver Seraphine: Won Canefield, a key Labour politician who later served as interim Prime Minister after the 1979 collapse, representing reform-minded governance.

- Romanus Bannis: Elected for the Castle Bruce Constituency; part of the Labour majority in 1975, contributed to rural infrastructure and community development efforts under the John administration.

- Ferdinand F. Parillon: Won the Colihaut Constituency; Labour representative involved in the coastal constituencies, underlining party reach into smaller districts beyond Roseau.

- Culand Dubois: Elected for the Cottage Constituency; served as part of the Labour government’s expansion of services into rural communities in mid-1970s.

- Patrick Roland John: Won Goodwill; party leader and Premier, central figure in the 1975 campaign and Dominica’s path to independence in 1978.

- Henckell Lochinvar Christian: Elected in the La Plaine Constituency; one of Labour’s vocationally-oriented representatives, emphasizing agricultural and local-economy policy.

- Victor Avondale J. Riviere: Won the Mahaut Constituency; part of the Labour legislative bloc facing rural challenges during the independent era transition.

- Eustace Hazelwood Francis: Elected for Newtown; later served as Speaker and Attorney General, influential in parliamentary development before independence.

- Randolph Bannis: Won Paix Bouche Constituency; held ministerial roles, later resigned amid the 1979 civil unrest, known for principled stance in turbulent times.

- Luke Taylor Corriette: Elected in Petite Savanne Constituency; younger Labour representative of the 1975 cohort, symbolising party renewal.

- Michael Douglas: Won Portsmouth Constituency; Labour figure in key coastal constituency, underlining the party’s strength in port towns.

- Bryson Joseph Louis: Elected for the Salisbury Constituency; part of Labour’s legislative majority, representing a small-district constituency in the north.

- Lawrence Darroux: Won the Salybia Constituency; one of the Labour members reflecting the party’s outreach to more remote parishes and indigenous areas.

- Isaiah Thomas: Elected in the St. Joseph Constituency; minister for youth/social security who died in 1977, honoured by school renaming, Isaiah Thomas Secondary School.

- Eden Bowers: Won the Vieille Case Constituency; Labour candidate who later became Speaker in 1979 during the crisis period, emphasising the party’s legacy.

- Osborne N. Theodore: Elected in the Wesley Constituency; Labour representative from a northern-coast constituency, part of the 1975 wave.

(Note: The full list of 21 members was documented in the 1975 parliamentary roll, which included all elected DLP representatives and ministers under John’s leadership.)

Governance and Ambitions

The Dynamic 21 symbolised a government eager to assert independence and expand Dominica’s industrial base. Their priorities included housing development, industrialisation through foreign investment, and a push for Dominica’s entry into the Caribbean Community (CARICOM).

The administration introduced major legislation, including the Social Security Act, Industrial Relations Act, and reforms to land settlement and national development. These measures aimed to strengthen labour rights, create jobs, and modernise Dominica’s economy.

However, internal divisions soon emerged. Some members questioned the government’s handling of trade union relations, press freedom, and proposed restrictions on workers’ rights. By 1978, tensions between the Labour government and the Dominica Trade Union movement escalated dramatically, culminating in national strikes and civil unrest that led to the May 29th 1979 Uprising.

The Decline of the Dynamic 21

The unity of the Dynamic 21 began to fracture amid growing discontent. In May 1979, several ministers, including Randolph Bannis and others, resigned following violent protests and attacks on government officials’ homes. Their departures weakened Patrick John’s government and contributed to its collapse later that year.

The collapse of the DLP administration marked the end of the Dynamic 21 era. Yet the group remains symbolic of a critical turning point in Dominica’s modern history: the transition from colonial rule to independence and from optimism to crisis.

Legacy

Despite its dramatic fall, the Dynamic 21 left a complex legacy. Members of the group played key roles in Dominica’s independence movement, public service, and later democratic rebuilding. Figures like Eustace Hazelwood Francis, Randolph Bannis, and Isaiah Thomas helped craft early post-independence policy frameworks. Others, like Oliver Seraphine, guided the country through stabilisation after the 1979 crisis.

The phrase “Dynamic 21” has since entered Dominican political vocabulary as both a marker of ambition and a cautionary symbol, representing a generation that promised transformation but was ultimately overtaken by the social and economic storms of its time.