DLP at 70: Survival, Strength, and the Shadow of Dominance

On June 1st, 2025, the Dominica Labour Party (DLP) will host a grand national rally in Dublanc to mark its 70th anniversary. With a line-up featuring local talent, quality production, and guest Prime Minister Mia Mottley from Barbados, the event is positioned to deliver cultural pride alongside national significance and unity. It is a deliberate and calculated show of strength by the island’s longest-ruling political party.

The DLP, founded in 1955, was originally grounded in the working-class ideals of Edward Oliver LeBlanc. Over time, it evolved into a political powerhouse. It has shaped or led the government for more than two-thirds of Dominica’s post-independence life. Under the current leadership of Prime Minister Roosevelt Skerrit, in office since 2004, Labour has consolidated its influence across institutions, public spaces, and electoral zones.

As Dominica prepares to enter another election cycle, the party’s 70-year milestone invites a closer look. How has DLP remained in power through tragedies, leadership transitions, and shifting voter expectations? And what does that continued dominance mean for the future of politics in Dominica?

A Party That Survived What Others Couldn’t

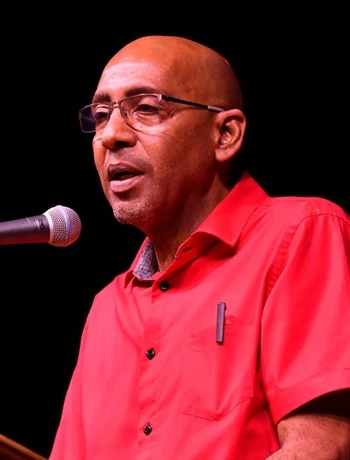

During a recent radio appearance on Political Pulse, Ian Douglas, Member of Parliament and Parliamentary Representative for the Portsmouth Constituency (Dos D’Âne, Bornes, Glanvillia, Portsmouth), recalled the turbulent early 2000s when DLP lost three of its national leaders while in office. His father Michael Douglas, uncle Rosie Douglas, and later Pierre Charles all passed during or shortly after assuming high office.

Rosie Douglas had only been Prime Minister for eight months when he died in 2000. He had reignited national hope and helped usher Labour back into power after years in the political wilderness. Pierre Charles succeeded him, but in 2004, he too died unexpectedly. It was a period that could have shattered any party.

Instead, the DLP reorganized. Ian Douglas credits the internal strength of the party, as well as a strategic pivot to younger leadership. That same year, Roosevelt Skerrit, then just 31 years old, became Prime Minister. It was a turning point. Not only did Labour survive, it entered a phase of consolidation and expansion that would define the next two decades.

As Douglas put it, “We were able to maintain the leadership and chart a new direction. That’s why we are here today, celebrating 70 years.”

From Crisis to Control

One reason DLP has outlived its rivals is its unmatched ability to organize. Over time, it has become more than a political party. It is a machinery with a permanent campaign structure. It knows every village, every voter, and every angle.

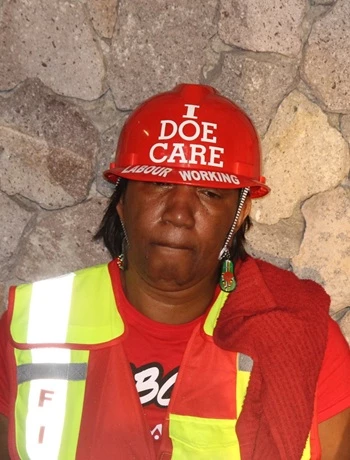

Political commentator Kamala Aaron described Labour’s structure on her weekly program Political Pulse. She praised the party’s event planning, discipline, and consistency. Her words, “They move with precision like a festival“, capture what supporters admire and what critics fear. That level of planning leaves little space for rivals to breathe.

The upcoming rally in Dublanc fits neatly into this pattern. It is a party celebration, but it is also a political message. In one afternoon, Labour will reinforce its presence in key constituencies, energize its base, and show the country that its momentum is still intact.

Critics may scoff at the symbolism. They may question whether stage lights and flags can feed families or fix roads. But for DLP, visibility is part of the message. If you are everywhere, your opposition appears to be nowhere.

The Changing Identity of Labour

Over the years, the ideological face of Labour has shifted. While the party was once openly socialist, advocating for worker cooperatives and state-owned development projects, modern Labour presents a more centrist, managerial approach. Development is now framed through infrastructure projects, diplomacy, and international grants.

This shift has created tension. For some, Labour has abandoned its founding philosophy. For others, it has simply adapted to modern governance.

Ian Douglas addressed claims that Labour’s strongholds, like Portsmouth, are kept in the family. He rejected the idea of political dynasty. “It’s a Labour seat, not a Douglas seat,” he said, emphasizing that the people vote for the party, not for his last name.

Still, the optics are hard to ignore. Labour’s long control in several constituencies has led to voter fatigue in some areas and accusations of entitlement. The challenge for the party is to retain loyalty while also proving that it can renew itself.

Young voters are asking new questions. They want results, not just rallies. They are less moved by slogans and more by opportunities. If Labour hopes to maintain its grip, it must prove that it can evolve in substance, not just in style.

What DLP’s Longevity Reveals About Dominica

The party’s ability to weather internal and national crises says something important about the state of political competition in Dominica. While DLP continues to strengthen its internal systems, the opposition remains fractured.

Over the past twenty years, Labour has won election after election, sometimes by wide margins, other times with coordinated constituency control. It has mastered both rural and urban campaigning. And despite criticism, it maintains popularity in key demographics.

However, this dominance comes at a cost. There are growing concerns about political balance. Critics argue that DLP’s command over resources and visibility has stifled genuine opposition. Others raise questions about transparency and blurred lines between party and state. They believe that when one political group remains in power for too long, it can create a culture of complacency and reduce institutional accountability.

As Labour prepares to celebrate its 70th anniversary, the rally in Dublanc will likely be a well-executed showcase of tradition and strength. But for the country, it is also a moment to reflect.

The question is not just how DLP has endured, but whether its continued dominance leaves room for political alternatives to grow. Can a true multiparty system flourish when one party functions more like an institution than a competitor?

And if the answer is no, what does that mean for democracy in Dominica?

This article is copyright © 2025 DOM767