Salisbury Declaration of 1976

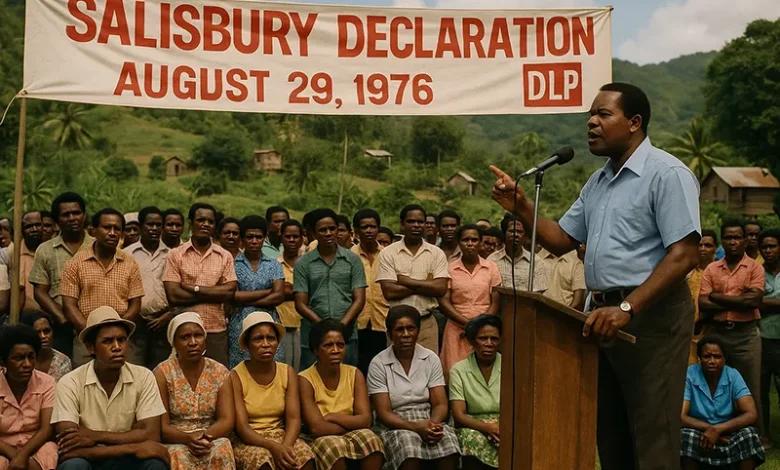

The Salisbury Declaration, announced on August 29, 1976, in Salisbury (Barroui), marked a critical turning point in Dominica’s path toward sovereignty. Declared by Premier Patrick Roland John at the Dominica Labour Party‘s annual convention, it officially communicated the government’s intent to pursue full political independence from the United Kingdom, with November 3, 1978, set as the prospective date. The event was more than symbolic; it laid out a legal roadmap and engaged national opinion in shaping the future constitution.

Historical Context and Political Climate

Dominica was an associated state of the United Kingdom in 1967, gaining autonomy over internal affairs while the UK retained responsibility for defence and foreign policy. By the mid-1970s, mounting nationalist sentiment coincided with economic pressures, including volatility in banana exports and public concern over sustained development. Premier John, leading a populist Dominica Labour Party, leveraged this backdrop to frame independence not just as political change, but as a means to address economic inequalities and national identity.

The Salisbury venue held symbolic resonance. It was once a thriving banana port and had previously hosted high-level political activities. The Declaration linked the daily lives of farming communities, such as Salisbury, to the broader agenda of self-governance and political empowerment.

Legal Provisions Under the West Indies Act

A central element of the Declaration was its specific invocation of Section 10(2) of the West Indies Act 1976. This path allowed Dominica to request independence by petitioning the British Crown, without requiring a referendum. At the time, Premier John noted that this approach mirrored Grenada’s experience and promised a more efficient route compared to Section 10(1).

John further pledged to publish a Green Paper, a formal consultation document to guide public engagement on constitutional options. The paper prioritised citizen input on governance structure, rights protections, and the monarchy’s role versus the republic. The goal was to ensure that independence would involve informed public consensus rather than a top-down decision.

Public Consultation and Constitutional Drafting

Following the Declaration, the government initiated a nationwide consultation campaign, culminating in the 1977 London Constitutional Conference, where delegates from Dominica, the UK Colonial Office, and regional observers drafted the Independence Constitution. Debates sprang up on several fronts:

- Whether to remain a constitutional monarchy under Queen Elizabeth II or to become a republic

- Whether to adopt a unicameral or bicameral legislature

- How to incorporate fundamental rights, including freedom of expression, assembly, and religion

- Defining the judicial structure, particularly the retention of the Privy Council or transition to a regional court

The Constitutional Order for Dominion status and independence was eventually signed in 1978, closely following the framework laid out in Salisbury the previous year.

The Text, Tone, and Political Messaging

Examining the tone of the original 12-page pamphlet, the Declaration emphasised: “Our island has sufficiently developed, morally and politically, to claim full membership among the sovereign nations.” It was both aspirational and pragmatic, grounded in the desire for self-reliance and the practical need to manage affairs, especially given existing national challenges such as economic vulnerability and external influence.

The Declaration was finalised with a formal parliamentary motion mandating the request for independence, and Premier John communicated the decision to the UK Secretary of State for the Colonies.

Legacy and National Identity

The Salisbury Declaration still holds a place of honour in national memory. It symbolises a moment when rural Dominica, represented by a banana port community, became the focal point for a national milestone. Educational institutions, civic programmes, and independence commemorations still evoke the Declaration’s spirit.

In 2015, political commentators directly referenced the Declaration during social activism, noting how Salisbury retained symbolic relevance in public life. Its issuance also impacted Constitutional interpretation, specifically in recognising consultative mechanisms and invoking legally valid processes under the West Indies Act 1976.