From Weed to Cocaine: The Crisis Dominica Refuses to Confront

- Cocaine use rising across Dominica

- Police wealth raises hard questions

- Youth addiction no longer hidden

- Drug money warps local economy

- Communities afraid to speak out

- No real rehab or state response

- Silence is fueling the collapse

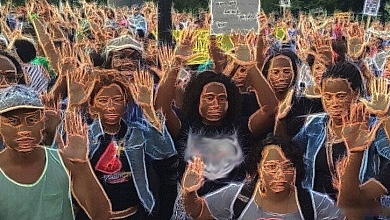

Walk through parts of Pottersville at night. Or pass through Newtown after school hours. Anyone paying attention can see it: drugs are no longer lurking in the shadows. They’re out in the open, part of daily life, woven into the corners of our communities. Not just marijuana. Cocaine too. And it’s not just a few wayward souls anymore, it’s young people leading the charge. Teenagers. Some as young as thirteen, some in uniform. This is Dominica’s quiet emergency. And we’re all pretending it isn’t happening.

There was a time when drug dealers stayed hidden. There was shame. There was fear of the police. Now, in some areas, it’s flipped. Some police officers themselves are suspected of dealing. There are men driving luxury vehicles, flashing wealth that does not add up to any known salary, and no one asks questions. In a small island like Dominica, everyone sees, but nobody speaks. Nobody wants to offend a cousin, a friend, or someone they grew up with. But that silence is costing us our youth. And it’s costing us our peace.

We’ve reached the point where some young people don’t even hide their use anymore. They treat cocaine like it’s just another cigarette. You smell it outside bus stops, by the bayside in Roseau, even near schools. There are reports of dealers operating comfortably in Bath Estate, Yampiece, Tarish Pit, Grand Bay, some even referring to it as “entrepreneurship.” In some places, you can’t tell anymore where the lines are between hustling and addiction. People laugh at the boys who sniff and talk to themselves in the street. But these are not jokes. They are casualties of a system that no longer cares.

There’s an entire underworld economy operating within our neighbourhoods. Youth, many of them smart, capable, and full of potential, are being sucked into a lifestyle that promises fast money but almost always ends the same: broken families, violence, prison, or a body on a cold slab. But yet, we act like we don’t know how they got there, as if they didn’t grow up in the same schools and villages we did. As if they didn’t try to find jobs and get turned away. As if the government didn’t know how many loopholes and blind eyes were built into this system.

The saddest part is that even some of those tasked with protecting us are suspected of playing both sides. When police officers are living lifestyles that their salaries clearly can’t support, and no one is investigating where the money comes from, what message does that send? It tells every young man watching that legitimacy is optional. That power protects power. That the rules don’t apply, and once that belief takes root, the door is wide open. You end up with communities that no longer trust law enforcement, and officers who see the street as an investment, not a duty.

We like to say “not all cops.” And that’s true. Good officers are trying their best with little support. But the silence from the top is deafening. When was the last time an officer was publicly investigated for unexplained wealth in Dominica? When did real prosecutions follow the previous major drug seizure? When a youth in Fond Cole gets arrested with a spliff, we hear about it. But the men importing kilos or laundering proceeds through fake construction projects? Nothing.

Just to be clear. This isn’t about condemning marijuana use. Dominica, like the rest of the region, is having an honest conversation about cannabis policy. But what’s unfolding now is far more dangerous. It’s the normalisation of hard drug use. Cocaine is no longer whispered about. It’s part of the nightlife in Roseau. It’s at house parties in Castle Comfort and Goodwill. It’s at the centre of fights, robberies, and domestic breakdowns in communities from Pointe Michel to Portsmouth. And still, not one public campaign exists to educate, intervene, or rehabilitate. Nothing.

And where there’s drug use, there’s dependency. And when the supply dries up, desperation fills the gap. People start breaking into homes, stealing from neighbours, or turning violent. We’ve already seen it. One addict looking for a hit can terrorise an entire block. They get laughed off as “parrow,” but the communities they destabilise are real. Their victims are real. The trauma they leave behind is lasting.

But who’s willing to talk about it? Not our ministers in government, they don’t want to offend voters. Not the churches, they’ve gone quiet, unless it’s about carnival. Not our leaders in the education system, who know exactly which students are slipping but feel powerless to act. And certainly not the police, whose silence can no longer be viewed as professionalism. It feels like complicity.

This is Dominica. A country small enough to know better and close-knit sufficient to fix it, if we wanted to. But we’ve allowed shame, fear, and convenience to become national policy. We’ve watched entire zones shift from tight communities to fragile spaces barely held together by secrets. And unless we break that silence, unless we demand answers and accountability, we will continue losing our children, one sniff, one spliff, one deal at a time.

No more pretending. No more brushing it off. Cocaine is not just a Roseau problem. It’s a Dominica problem. And we need to start acting like it.

This article is copyright © 2025 DOM767