From Colonial Rule to Political Routine: Dominica’s Quiet Drift

What Dominica Forgot to Deconstruct

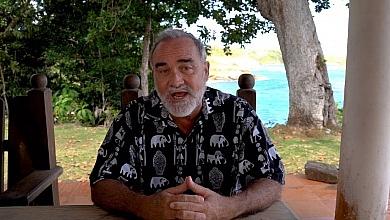

In 2022, during a commemorative lecture marking 52 years since Dominica gained internal self-governance, historian and cultural adviser Dr. Lennox Honychurch delivered what many might have passed off as a routine reflection on national history. But revisiting the content today, amid economic pressure, political tension, and infrastructural fragility, it reads more like a sober reminder that Dominica’s past has always been entangled with its present challenges.

This wasn’t a lecture about personalities or nostalgia. It was about institutional design, colonial inheritance, and the unfinished business of post-independence transformation. The address, hosted at the UWI Open Campus, offered a methodical walk through the historical architecture of Dominica’s parliamentary system. More importantly, it outlined a pattern of avoidance: the failure to restructure state institutions when we had the chance.

Self-Governance: A Window That Never Opened Wide

Dominica’s 1967 transition to internal self-government under the West Indies Act gave the island substantial autonomy. But the apparatus of government, laws, bureaucracies, administrative protocols, remained largely colonial in origin. Dr. Honychurch traced how the post-1967 leadership, while vocal about self-determination, retained these inherited systems without modification.

Today, the implications of that decision remain visible: a top-down administrative state, weak systems of public consultation, and governance structures that lean heavily on executive authority.

In the lecture, the point was made clearly: “we inherited institutions shaped by imperial rule and merely localized their management.”

This historical continuity raises difficult questions. If the foundational design of our public institutions was never reconsidered, what did we really change? And can we keep blaming foreign legacies for current governance failures when reform has long been in our hands?

Missed Opportunities at Independence

When Dominica moved from self-governance to full independence in 1978, the new Constitution came into force. However, as Honychurch noted, it mostly preserved the Westminster-style governance model with only cosmetic modifications. The real debates of that time, about decentralization, economic autonomy, or participatory democracy, were largely sidelined. The priority then was political unity in a time of economic uncertainty. The banana boom was nearing its end. The Cold War was heating up in the region. Dominica had barely emerged from the chaos of 1974–75 protests. The prevailing instinct was to maintain order, not experimentation.

In hindsight, this pragmatism created a vacuum in public life. Instead of imagining a different model for governance and accountability, we reinforced centralism. Ministries became even more powerful. Parliament remained largely adversarial. Public service was professional but not citizen-driven. Honychurch’s remarks served as a subtle critique of this trend: nation-building, he implied, was narrowed to managing what was inherited, not reimagining what was possible.

Development Without a Deep State

Another point raised in the 2022 lecture was the notion of “development” as practiced in Dominica, often driven by foreign aid, outside expertise, and electoral cycles rather than long-term national planning. Honychurch didn’t say it outright, but the implication was there: Dominica lacks the kind of deep institutional architecture that supports continuity, policy feedback, and civic participation.

This insight feels particularly relevant today. Whether one considers the stalled electoral reform process, the challenges in post-disaster housing delivery, or the growing complexity of climate resilience planning,what emerges is a system stretched thin by reactive governance.

Even our economic sectors, tourism, agriculture, infrastructure, are guided more by projects than by strategies. The public service, once a respected technocratic body, has been increasingly politicized. And regional integration efforts like CARICOM are treated as external obligations rather than integral planning tools.

The lecture asked a subtle question we’ve yet to answer: “Have we built a country that runs only when a charismatic leader is in charge?” The evidence remains troubling.

The Political Culture We Inherited, And Accepted

Honychurch’s reflections also returned to political culture. He noted how deeply the colonial model of executive dominance, through Governors and Legislative Council, has embedded itself in how modern politics functions in Dominica. The public often sees politics as a contest of personalities, not policies. Campaigns focus on loyalty, not long-term platforms.

Fifty-two years after gaining internal control of our affairs, this model persists. The office of the Prime Minister, an invention not found in the 1930s, is now the most centralized point of power. Ministers wield extraordinary discretion over project selection, resource allocation, and even recruitment in public institutions.

Attempts at reform have come and gone: from proposed local government restructuring to constitutional amendments. Most have failed or been shelved. The electorate, meanwhile, is caught between cynicism and clientelism, too often demanding personal favors instead of institutional guarantees.

Toward a More Deliberate Future

Perhaps the strongest reminder from the 2022 lecture is that reform is always a choice. It’s not imposed by London or dictated by Washington. If Dominica remains governed by 1960s logic, it is because we allow it. If our public institutions continue to serve ruling parties more than the population, it is because we do not demand better. Honychurch pointed to Caribbean models that have tried alternative approaches, Barbados’ administrative reforms, Jamaica’s investment in local government, Grenada’s attempts at constitutional review. Each has faced setbacks. But each has tried. Dominica’s approach has been less courageous.

We continue to expand the executive while weakening local governance. We centralize planning but underfund community organizations. We emphasize “resilience” but ignore institutional brittleness. This, more than anything else, is what the lecture reminded me: that governance is not only about elections or ministers. It is about systems. If those systems remain unreformed, no matter who is in charge, our progress will be built on sand.

Final Thoughts: Independence Without Internal Democracy?

Looking back, one wonders whether we mistook independence for liberation. What we achieved in 1978 was political sovereignty. What we failed to achieve, what we still fail to achieve, is institutional autonomy.

The lecture from 2022 didn’t call for revolution. It called for self-awareness. It asked that we stop treating colonial rule as a past era and begin recognizing it as a present influence. It suggested that independence is not something won once, but something renewed through reform.

As Dominica enters its 47th year of independence, the warning remains: without serious introspection about how we govern ourselves, we will continue to repeat patterns dressed in national colors. We will remain a postcolonial state that governs like a colonial province.

And history, as Honychurch reminded us, does not reward those who confuse continuity with stability.

This article is copyright © 2025 DOM767