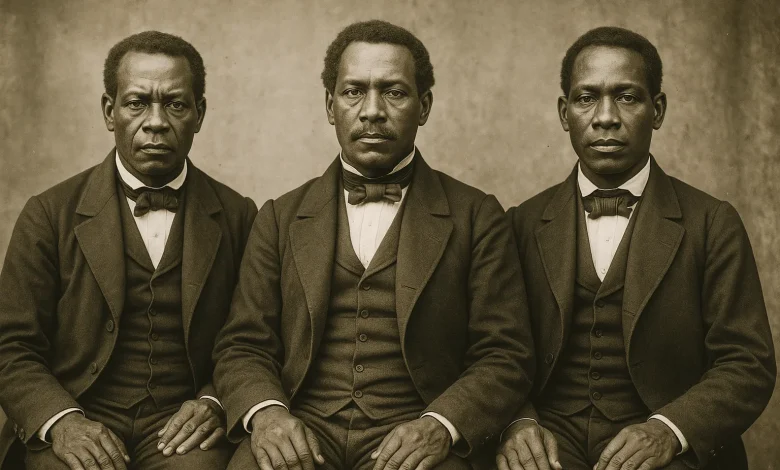

Black Legislature of Dominica (1838)

Black Legislature in 1838 describes the brief period after emancipation when Dominica’s elected chamber was controlled by representatives of African descent. The outcome followed the Slavery Abolition Act 1833, apprenticeship beginning in 1834, and full freedom on 1 August 1838. Contemporary summaries and later histories agree that by the end of 1838, Dominica stood out as the only British Caribbean colony in the nineteenth century with a legislature led by a Black majority, drawn largely from free people of colour, smallholders, and merchants.

Background and Pathway to Majority

From the late 1820s reforms widened the Franchise for free people of colour. In 1832 three men of African descent entered the House of Assembly, foreshadowing the post-emancipation realignment. The apprenticeship years maintained plantation discipline but also accelerated civic participation, and when apprenticeship ended on 1 August 1838, voters returned an Assembly in which Black and coloured representatives held control. Sources emphasize that these legislators typically owned small properties or ran town businesses and advanced policies that diverged from the interests of the older planter elite.

The chamber’s composition reflected new social power after Emancipation. Members pressed for measures associated with a peasant and urban artisan base: protection of Provision Grounds, fairer taxation, improved access to markets such as Old Market in Roseau, and constraints on estate control over local policing and passes. Planter interests resisted, arguing that estate recovery and export revenues required priority. This friction soon migrated into constitutional design. The imperial preference for mixed chambers led to experiments that diluted the popular majority through nominated seats in the Legislative Council of Dominica, a pattern documented across the region when planter influence waned.

Constitutional Rollback

Dominica’s Black majority was historically singular yet short-lived. In mid-century the constitution was altered to split representation between elected and appointed members, and in the 1890s Britain re-established Crown Colony Government, ending effective local control by elected representatives. Timelines commonly note 1865 for a half-elected half-appointed arrangement and 1896 for full Crown Colony rule. These changes placed decision-making with governors and nominated councils and sharply narrowed the role of the Assembly, reversing the democratic opening that followed 1838.

The 1838 majority matters for three reasons. First, it links the legal milestones of Abolition of Slavery in Dominica to immediate political change, not only social change on estates and in markets. Second, it demonstrates how property-holding small farmers and town merchants could translate new rights into legislative authority under the existing Property Qualification rules, even while wealth and land remained unequally distributed. Third, it anchors a distinctive island narrative inside wider Caribbean history, where other colonies moved to restrict rather than expand popular influence after emancipation. Historians and government summaries repeatedly single out Dominica’s case as unique in the nineteenth-century British Caribbean.

Timeline

- 1832 Three men of African descent elected to the Assembly under widened civil rights for free people of colour.

- 1 Aug 1834 Start of apprenticeship following the Slavery Abolition Act 1833.

- 1 Aug 1838 Apprenticeship ends. Assembly controlled by Black and coloured representatives becomes the regional outlier for the century.

- 1860s Mixed constitutions reduce electoral dominance through appointed seats.

- 1896 Crown Colony rule re-established, consolidating executive and nominated council power.